“We must act now—right now—to tackle climate change. It’s one minute to midnight on that doomsday clock.”

That isn't a quote from Ed Miliband, the embattled Energy Security and Net Zero Minister, nor Zack Polanski, the freshly elected, self-described eco-populist of the Green Party. That’s actually a quote from Boris Johnson while he was Prime Minister. The fact that comment feels so jarring demonstrates just how far the mainstream has moved from the cosy consensus on climate action and net zero (a legal target introduced by the Conservatives in 2019).

In late 2025 we have both Reform (who were 92% funded by fossil fuel interests between 2019 and the 2024 election) and the Conservatives being explicitly anti-net zero, anti-climate action and even anti-climate science. Senior figures in the Labour Party appear to be looking for an excuse to distance themselves further from a set of policies which were once the centrepiece of their pitch to voters – despite the positive vision set out in their recently-published Warm Homes Plan.

In truth, there has been growing disquiet over net zero and climate policies for some time and, as the transition encroached further into peoples' lives and began to influence how they heated their homes, moved around and what they ate, a compelling positive case for action was going to have to be made.

It can feel like the battle has already been lost, that we (and perhaps our closest friends and relatives) still care about climate but no one else really does. New, detailed polling from the excellent Climate Outreach Britain Talks Climate and Nature report, demonstrates this isn’t the case. They found that 74% of respondents felt climate change was an important issue. However, their research also found that the public feel deeply disillusioned.

They state:

“People feel overlooked, disillusioned about the present and fearful for the future, and many are yet to be convinced that net zero offers a positive way forward.”

This gap, between how individuals feel people other than themselves think about nature and climate change, and the reality set out in Climate Outreach’s report, where we can see nature and climate remain major concerns for a significant majority, has a name – pluralistic ignorance – where we significantly underestimate others’ levels of concern about an issue. This, coupled with widely felt disillusionment and distrust of institutions and decision-makers is a harmful phenomenon as it leaves us feeling isolated, prevents us having the conversations we need to be having, hinders positive action and leaves the door open to anti-climate rhetoric that is falsely assumed to be the majority view.

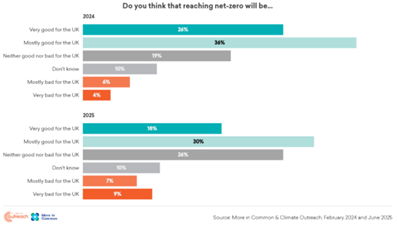

The Climate Outreach findings begin to point to solutions to this issue. They’re an organisation concerned with climate communications, and they suggest it is critical that public figures 'translate and explain, don’t assume or assert’. This means cutting down on technical jargon, but most importantly, communicating in clear and inviting ways which describe enthusiastically why a policy matters and what it means for people’s lives. They recommend focusing on wider benefits of climate action and to remember that most people still believe achieving net zero will be good for the country (while not taking this support for granted).

This analysis feels broadly correct and anyone interested in these topics should definitely look at Climate Outreach’s work for deeper insights. Pairing environmental and economic/social concerns has to be the way forward.

When the British public are polled on what the most important issues facing the country are, they consistently rank some combination of Health, Immigration, The Economy, and Crime in their top 5 with the 5th spot taken by one of Tax, The Environment, Housing, Welfare or Defence. I would argue that nature and climate have a relationship to each of these, either because the impacts of climate change and collapsing ecosystems exacerbate these issues, or because well-designed policy to address them (i.e. building or retrofitting homes, encouraging the adoption of low cost public transport, supporting local, low carbon economies, etc) will have a material impact on mitigating or adapting to climate change and nature loss. There’s evidence of this fusion of climate action with progressive economic thinking taking place, with prominent left of centre think tanks and commentators now consistently making this case. We’ve also seen Friends of the Earth appoint Asad Rehman, whose previous role was head of War on Want, as their new CEO. Switched-on politicians and public figures would do well to apply this kind of eco-populist framing to their campaigns and policymaking.